I’ve written elsewhere about the age-old romance between the wine vine and trees, and of the numerous ways in which the two have interacted over the centuries. It’s understandable that this symbiosis goes mostly unnoticed today since vines are no longer trellised on stately elms, as was once common. But trees and vines are still a team.

I’ve written elsewhere about the age-old romance between the wine vine and trees, and of the numerous ways in which the two have interacted over the centuries. It’s understandable that this symbiosis goes mostly unnoticed today since vines are no longer trellised on stately elms, as was once common. But trees and vines are still a team.

Many wines benefit from time in barrel, mainly because tight-grained wood does a good job of protecting them from outright oxidation, thus maintaining freshness, while simultaneously admitting the minuscule amounts of oxygen needed for wine to mature properly.

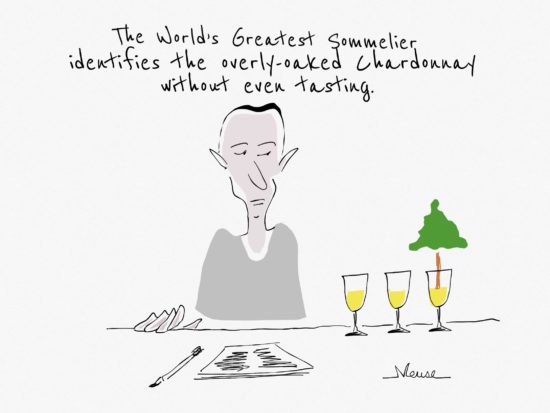

When the barrel in question is of oak and freshly made, it can alter the character of the wine it holds. It’s above all New World chardonnay that is often identifiable by this single characteristic – being distinctly and emphatically “oaky.” It’s a profile not easily missed even in so-called blind tastings.

These woody scents and flavor notes added by aging in new, as opposed to older, oak barrels, eventually became so associated with certain chardonnays that even wines that didn’t have price points capable of supporting the high cost of new oak casks had to find a way to mimic the effect. And ways were found, even if some of them aren’t very nice to talk about.

They include scraping the inside of old barrels to expose fresh wood, suspending staves of new wood in older casks; oak “beads,” shavings — even sawdust, collected into a large sachet that can be suspended inside a vat like a Brobdingnagian teabag.

You might think that this sort of behavior on the part of winemakers is the more or less inevitable outcome of modern capitalistic production techniques, but additives intended to augment or frankly alter the natural flavors of grape wine are pretty much as old as winemaking itself. We know for example that our first collective attempts at fermenting fruits involved throwing anything sugary into a pot, along with whatever other ingredients were thought likely to make a positive contribution to the final product.

The great first century Roman naturalist, the elder Pliny, offers us a long list of wine additives in use in his day. Some were aimed at preserving wine or covering faults, but others seem to be there just because people liked the taste, or said they did. Included in his inventory of the ancient vintner’s pantry are wood ashes, gypsum (still in use as a deacidifying agent, by the way), barley, myrrh, seawater, cassia, cinnamon, pepper, honey, wormwood, hyssop, wood smoke and lead (a sweetener).

Perhaps, over time, the sensations produced by this roster of outlandish ingredients became markers of quality wine — something that people looked for and were disappointed not to find, rather like the spicy, buttery flavors recently in vogue for chardonnays. It seems useless to apportion blame for any of these behaviors, ancient or modern, since they seem to owe so much to taste, which is always in flux. It’s vain to speculate what moved someone in a bar in Pompeii in 70 A.D. to order wine mixed with seawater drawn from the nearby Bay of Naples. We just don’t know.

It may be that once wine was fully incorporated into everyday Mediterranean life, its consumers felt a need to make it a bit less common by dressing it up with exotic mix-ins. It may have been thought of as a kind of customization, like the trim levels in a new Passat, so that you weren’t seen to be downing the same plonk as the rustics at the next tavern table.

At the moment, we seem to be moving swiftly in the direction of a new taste paradigm, one in which prestige attaches not to wines with a high degree of post-fermentation polish and added drama, but instead to those made in the purest, simplest, least elaborated way.

For those who espouse this new standard, finishing in new oak adds a layer of distance between us and the original vineyard material that they would sooner do without. As a result many contemporary wines are finished in cement, glass, or terra cotta — all of which make less of an impact on flavor and texture.

Tastes may well be undergoing a seismic shift, but I don’t think we’ll ever see oak entirely disappear from the cellars of winemakers. And that’s a good thing, since one of the most objectionable things about woody wines has been their ubiquity. In wine, as in so many other areas, diversity is a fine and welcome thing. A discrete note of savory oak remains a real pleasure for me, and I wouldn’t want to see it exit the stage entirely.

It’s always possible that the day will come when oak will, in retrospect, seem as egregious a trespass as an addition of hyssop or ashes. But if it does happen, I won’t be the only one prepared to take things into his own hands.