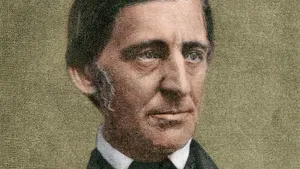

”A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” Ralph Waldo Emerson (that’s the old troublemaker himself, above) memorably opined. But in the world of commerce, consistency is pretty much everything — the very hallmark of the branded product. Many perfectly reputable wine estates aim at achieving it. Historically, the wine world’s most accomplished practitioners of this have been the bigger Champagne, Port and Sherry houses which have long been on a first-name basis with this particular hobgoblin.

”A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” Ralph Waldo Emerson (that’s the old troublemaker himself, above) memorably opined. But in the world of commerce, consistency is pretty much everything — the very hallmark of the branded product. Many perfectly reputable wine estates aim at achieving it. Historically, the wine world’s most accomplished practitioners of this have been the bigger Champagne, Port and Sherry houses which have long been on a first-name basis with this particular hobgoblin.

Opposing this approach are most smaller-scale, artisan wine producers, who, working in facilities that are more like a workshops than factories, maintain consonantly different priorities. Among them, a decidely non-technical approach, a personal creative vision, and an emphasis on what we might call the place-dependence of wine character. For this group, consistency appears more like mandated monotony; variation from vintage to vintage and even bottle to bottle are things to celebrate, not run from. The American philosopher and moralist known as the Sage of Concord could be their patron saint.

But, hang on. If the durable features of a vineyard (site, soils, exposition, native yeast populations, etc.) are primarily responsible for the distinctive features of a given wine, and if one purpose of wine is to express this specificity, shouldn’t we expect to encounter some measure of stability of character from year to year — even from generation to generation?

We think the answer is a qualified yes, but rather than risk aggravating the squabble over the value of consistency by taking sides, we suggest reorienting the conversation — away from replication and toward continuity.

Continuity doesn’t imply the kind of machine-like precision associated with mass-produced goods. Its constraints are less confining, its contours softer and more graduated. As a guiding standard, it’s far more forgiving of experimentation, creativity and variety.

While continuity respects historic benchmarks of style and quality, it needn’t be bound by them. It doesn’t adhere slavishly to idealized norms. It shoots for the sort of resemblances we find in nature, wherein species have identifiably familiar features, without individaul members being identical.

As a concept, continuity provides a way to both think about and bring about wines that have a connection to place while still providing them room to roam; a path out of the small-minded rigor that bedevils wine more than it should.

Its inherently more generous terms might also make us all a bit less prone to the kind of foolishness that so irked Ralph Waldo. We imagine he would appreciate that.

—Stephen Meuse