Exactly what too far may be will always be a matter of taste and judgment, but at this point in the evolution of wine-with-nothing added-and-nothing-taken-away, we’re pretty much over the idea that we should be drinking someone’s failed experiments. The very good news is that we’re seeing cleaner, healthier, more drinkable examples of the genre every week.

It may seem odd to say it, but there is one sense at least in which natural wine is anything but natural. By this I mean that there’s no way to go about the making of it that can be said to be purely intuitive or spontaneous. It can’t be done by beginners or neophytes without a lot of direction. Even for experienced vintners there’s a learning curve that’s more slope than steep

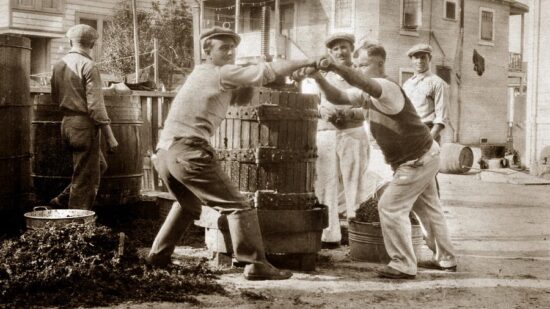

No matter what you’ve heard, it’s not just a matter of crush the fruit, throw it into a pot or vat of some sort and come back a few weeks or months later. It doesn’t work this way for a very simple reason: Wine isn’t something nature (pardon the anthropomorphism) does on purpose.The production of fruit of any kind is part of an ingenious plant reproductive scheme that we humans take advantage of in numerous ways, but which wasn’t designed to be of use to us.

One way to describe it is to say that nature gives the apples but not the apple pie — the production of a delectable tarte de pommes being quite irrelevent to its crude, existential aims; the furthest thing from its mind, if it had one. Thus, nature gives the grapes, but not the wine, right? Maybe not even that.

I’ve written about the wild grapes that climb the trees that line the backcountry road we walk when in our favorite corner of Vermont at the end of each summer. Small, scant, hard, barely ripe and largely juiceless, they may please the birds who graze on them, spreading their seeds and genetic material far and wide. But it would be impossible to make anything but a meager and thoroughly disagreeable wine from them.

Wine grapes that exist today are a far cry from anything natural processes could produce unaided. On the contrary, the maker of the most natural wine in the world (whoever that might be) begins every vintage with vines that are the product of something like 8000 years of diligent human selection and propagation.

In this sense, every winemaker who has ever lived has been or is currently the beneficiary of generations of sunk costs in ingenuity, experimentation and labor. It doesn’t have to have always been scientific. In this field, the oral transmission of what we today call best practices is centuries-old; much of it still sound and useful. It only seemed natural because when we encountered it, it was already there — a fallacy frequently met with and just as frequently escaping notice.

Speaking of science, the fact that we can today work successfully in more naturalistic ways owes pretty much everything to our advanced understanding of, and ability to manage, microbial life. If fermentations were still the mystery they were before the 19th century investigations of Pasteur, stable, durable, ageworthy wine wouldn’t be impossible, but likely would remain the crapshoot it had always been.

Slowly, we’re learning to make wine without recourse (or less recourse) to additions of the sulphur that for most of history has been wine’s salvation. The degree to which natural wine is made possible by people in laboratories has always seemed to me a delicious irony.

We come to praise natural wine, not bury it. Not only do we love to drink ( and sell) its best examples, we share its aspirations and admire the dedication of its good faith disciples. Let’s just try to keep its claims within the bounds of what we know to be true of wine’s long history.