Oak barrels have been important in winemaking for a very long time, and the spice and vanilla flavors they impart are by now familiar. The drama added by aging in new oak became so associated with prestige California Chardonnay that even wines without price points capable of supporting the cost of fresh casks each vintage had to find ways to mimic the effect. And find them they did. Techniques include scraping the inside of old barrels to expose fresh wood, suspending a few staves of new oak into older casks, adding wood beads or shavings — even sawdust suspended in an oversize teabag. Not that nice to talk about.

You might think that this sort of behavior is just the inevitable outcome of modern capitalistic production, but maneuvers of this sort are truly as old as winemaking. Some were aimed at preservation or concealing faults, but others seem to have been adopted just because people liked the taste (or said they did).

Included in one ancient inventory of the vintner’s bag of tricks are wood ashes, gypsum (still in use as a deacidifying agent, by the way), barley, myrrh, saltwater, cinnamon, pepper, honey, wormwood, hyssop, pitch, wood smoke, and lead (a sweetener). It’s vain to speculate about what prompted someone in a 70 C.E. Pompeii dive bar to order his wine mixed with seawater drawn from the nearby Bay of Naples. We just don’t know.

At the moment we’re moving swiftly in the direction of a new paradigm of quality, one in which prestige attaches not to wines that have been subject to exotic flavoring agents or technical legerdemain, but to those made in the simplest, least elaborated way. For those espousing this aesthetic, aging in new oak is little more than an obstruction — sensory clutter blocking our view of the all-important underlying material.

As a result, many quality contemporary wines are never subjected to its influence. Stainless steel, cement, clay and glass are increasingly common, neutral, alternatives.

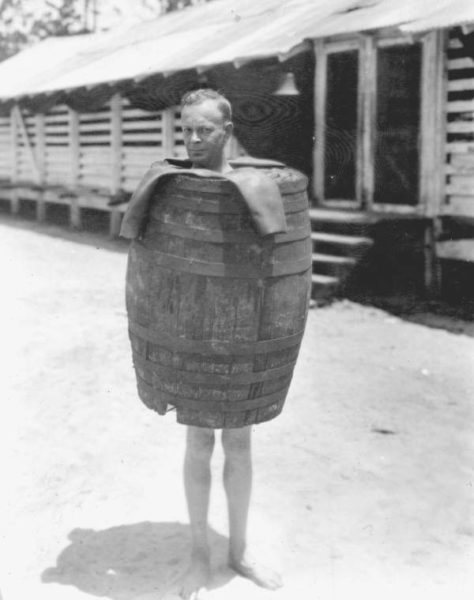

Tastes may well be undergoing a seismic shift, but I don’t think we’ll see oak disappear from the cellars of winemakers anytime soon. And that’s good. In wine, as in so many other areas, diversity is a fine and welcome thing. A subtle grace note of oak remains a pleasure for me, and I wouldn’t want to see it exit the stage entirely. It’s always possible that the day will come when wood-soaked wine will seem as egregious a trespass as a dollop of hyssop or ashes. But if it does happen, I won’t be the only one prepared to take things into his own hands.

-Stephen Meuse