Is wine good for your complexion? Can it adjust your temperament? Balance your humors? Don’t be embarrased If you haven’t asked yourself these questions recently. Most people haven’t, at least for the last hundred and fifty years or so. But before that, it was a different story. Here’s how it goes.

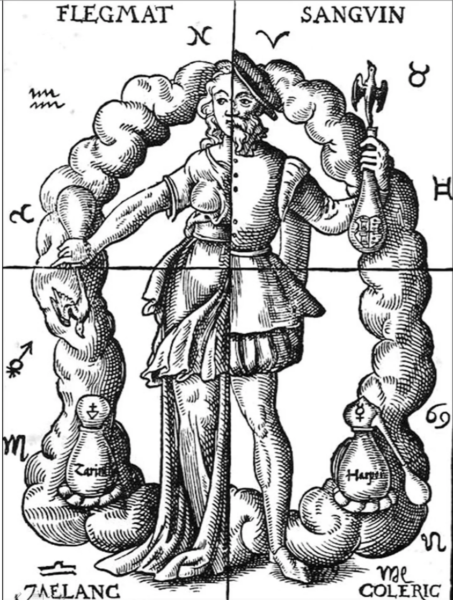

For most of literate human history, both medical practice and everyday ideas about what constituted good health were guided by something called humeral theory; the notion that four major fluids were at work in the body and that their balance relative to each other was responsible not only for your general condition, but the way you looked and behaved.

All four survive today mainly as words that describe personality. We still refer to people with a generally hearty, cheerful disposition as sanguine, darkly moody people as melancholic, the easily angered as choleric and the listlessly conforming as phlegmatic. In the theory’s salad days, these weren’t just colorful terms, they were the reigning paradigm of the healing arts. The system’s popularity and amazing durability lay in its simplicity and explanatory prowess.

For example, it wasn’t just individuals who had a temperament (as these types were called), displayed in a specific complexion (overall appearance; eye, hair and skin color). In early (regrettable) efforts at racial stereotyping, whole peoples were thought to participate in a common temperament, depending on the prevailing conditions in the lands they inhabited.

It wasn’t just the physical condition that was in view. Humors ruled mental states, too and were responsible not just for variations in individual character but, by extension, could serve to explain entire cultures. The Dutch were generally phlegmatic, it was thought, while Brits tended toward the melancholic.

Moreover, premodern medical treatment (apart from amputations, trepanning and bone-setting) consisted almost solely of maneuvers intended to reset the balance of humors, something that was accomplished primarily by diet. This meant that every known ingestible had to be investigated and judged for its ability to tip the scales one way or the other and assist in re-establishing a salutary equipoise.

Herbalists accordingly classified every known plant by its tendencies to promote, counter or adjust the humors. Thus melancholy (a cold, dry humor) could be amended by applications of, say, red wine, which was considered warm, wet and tending toward the sanguine. While white wine (cold and wet) might be prescribed to offset a tendency toward the choleric (hot and dry).

Wine’s historic role in the arsenal of the premodern physician wasn’t restricted to its use as an agent of humeral rebalancing. It was for centuries the medium into which medicaments and drugs of all kinds were routinely mixed and delivered to the sufferer. If the idea of wine as medicine seems rather quaint to us moderns, let’s not forget wine’s recent (and in some quarters ongoing) fling with celebrity as a sovereign prophylactic against cardiac and vascular disease (see my The New French Paradox for a recap).

As for the state of your correspondent’s humors, and the degree to which they may be responsible for what appears in this space from week to week, we take no position. But his wife will testify that when a little out of sorts, and pouring himself a small glass of wine with the aim of putting himself right again, he may frequently be heard to quote St. Paul’s admonition to his young friend Timothy:

Drink no longer water, but use a little wine for thy stomach’s sake and thine often infirmities.