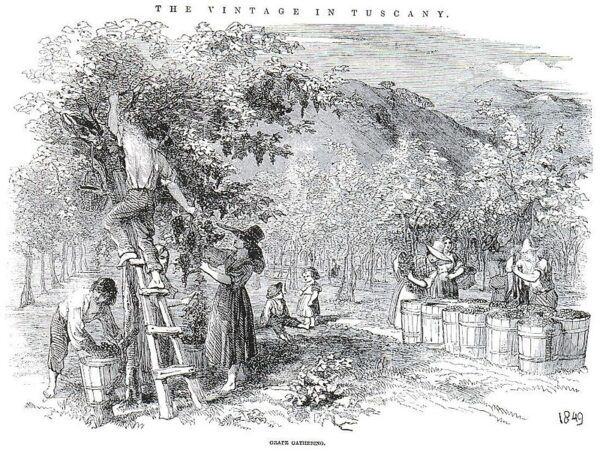

Birds gotta fly, vines gotta climb. It’s the way of things, and for most of the history of winemaking, it proved convenient to give domesticated grapevines the opportunity to do what comes naturally to them in the wild by planting them alongside trees. The advantages of this strategy are obvious. A vine that could embrace a sturdy tree trunk for support need not put energy into developing one of its own. That the ripening fruit was out of the reach of passersby (varmint or human) was a bonus. In truth, vines whose fruit is destined for winemaking have been leaning on trees pretty much forever — and not just for physical support.

Bundling the discarded canes collected during pruning calls for sturdy cordage. To provide it, growers planted groves of willow, whose long, strong, flexible branches proved ideal for the task. Meanwhile, the tree’s notoriously thirsty roots took up water in places that would otherwise have been too poorly-drained for use as vineyards. Marcius Portius Cato, writing in the 3rd century BCE, explains the value of lining wine storage vessels with the pitch of the Terebinth tree. The resin served the dual purpose of preventing leaks and introducing an anti-spoilage agent (resins were also used to prevent sepsis in wounds). Cato doesn’t discuss the influence that pitch-lined casks had on wine flavor, but, 200 years later, Pliny the Elder named it as an ingredient that could be used to impart a “smoky” note that was apparently prized in his day.

Later, when the Romans had established vineyards in northern Europe, the romance of tree and vine took a torrid new turn — in the form of the wooden barrels that replaced clay amphorae as the common fermentation and storage vessels for wine. Oak, chestnut and acacia tuns made their own contribution to the character of wine by supplementing primary fruit flavors with mature, barrel-y notes and with tannins that added structure and texture.

Today we have lots of cheaper, cheesier ways of getting woody flavors into wine (staves, nuggets, beads, sawdust) but even these techniques are hardly newfangled. In his agricultural treatise of 1600, Olivier de Serres suggests that cadging wood chips from the local carpenter and adding them to maturing wine (or wine that was starting its inevitable slide into vinegar) made it last longer and taste better — noting slyly that this was a trick every savvy innkeeper in France knew. But even then the tree wasn’t done doing favors for the vine.

The ubiquitous cork stopper is made with the ever-renewing bark of quercus suber, a species of oak. Its union with the glass bottle in the 18th century revolutionized the way wine was purchased, stored, and enjoyed. For the first time an individual with little room could store wine, safely, long term. The conveniently-sized container facilitated a slow, even maturation of its contents and didn’t put the whole of the owners’ stock at risk of spoilage when it was cracked open, as was the case with barrels. The bottle and cork tandem effectively, if gradually, shifted tastes away from the relatively simple flavors of fresh fruit toward the more complex experiences provided by wine that had spent years in bottle.

No, wine doesn’t grow on trees – but it surely wouldn’t be the same without them.