This week’s New York Times magazine featured an interview with that Moses of U.S. specialty importers, Berkeley-based Kermit Lynch — and it’s well worth your time. Lynch was an early advocate of what we would now call terroir wines, but has never been a terroiriste. By this I mean that, so far as I know, he never really tried to articulate precisely what made the wine he stumped for appealing, nor has he ever issued comprehensive, dogmatic statement on terroir as the Wine Spectator’s Matt Kramer has.

Lynch was also one of the first Americans to tramp the backroads of France’s wine country, knocking on doors and tasting in cellars that had never admitted an outsider before. His 1988 book Adventures on the Wine Route is wonderfully entertaining. It was instrumental in shaping my own idea of what constituted quality and proportion in wine and made me deeply skeptical of the alternative view being presented by Robert Parker Jr., then just coming into his own.

A story I enjoy recalling suggests another reason I’m so fond of the book. It concerns being seated next to Prince Philippe Poniatowski of Clos Baudoin (now under the ownership of Francois Chidaine) at a wine-tasting lunch in Cambridge when I was just starting out in wine writing.

Poniatowski was old Polish aristocracy, a distinguished and debonair 70-something, and a reputed war hero. He was sociable enough and his English was impeccable but the prospect of having to converse with him for the duration of the event was daunting. What, I wondered, would we chat about?

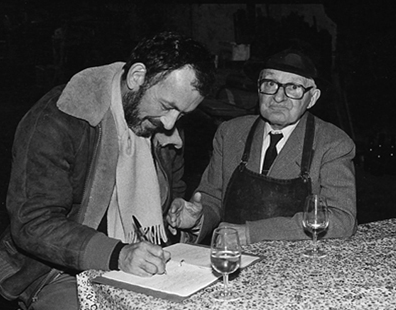

Clos Baudoin is in Vouvray, and it came to me that Kermit Lynch had devoted an entire chapter of Adventures to a particularly colorful character there: a negociant known as Père Loyau. I dropped the name. Yes, the prince knew him well, seemed surprised that I was acquainted with him (I never said how), and proceeded to regale me with several wonderful anecdotes about the old man. Though deceased by then, Loyau had still been active at age 100.

The vintner-prince and I went on to have a lively, and for me memorable, two-hour chat. It didn’t hurt that I knew a Poniatowski had accompanied Napoleon on the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812.

Lynch’s book is about to be re-issued. An ebook can be downloaded here for around $12. Read the entire Times interview with Kermit Lynch here.

* * * *

I was recently reminded while discussing the effects of bottle age with a Central Bottle guest of how very old wines come to resemble very old people.

The notion came to me one night a few years ago while tasting some very old wines with friend Len Rothenberg of Federal Wine & Spirits and a group from the Erni Loosen team, including Loosen himself. I noticed that the older the wine the less consensus could be mustered around its identity. One in particular caused consternation: a wan, mahogany-tinted relic of what must once have been a vibrant, ruby-hued red wine. It was still an engaging sip – but the usual clues to provenance were long gone.

“Pinot,” someone bid without much conviction. “Cabernet, probably Bordeaux,” offered a couple of others. In a group or very experienced tasters, no one was willing to insist on his opinion since whatever varietal or regional character had once been there was overwhelmed by the aromas and flavors of bottle-age. More than anything else, it was a generic old red wine.

In the midst of this discussion, I floated the following idea: wines are much like people. As men and women age, those things that define us, made us individuals, set us apart as distinct characters recognizable to our longtime friends and family, tend to fade until at some extreme point we’re barely recognizable as personalities. We become generic old people.

Hard of hearing and dim of eye; with the hormones that once highlighted gender-specificity drained away; eventually not even distinguished by the cues provided by dress or how we cut our hair, we all – assuming we live long enough — lose our individuality and decline into indeterminateness. Not men, not women; neither witty nor dull, skilled or clumsy; no longer by temperament either cheerful or morose. Just plain old.

Pulled at last from its brown paper bag, the wine was revealed to be a 40 year-old Cote Rotie from Marcel Guigal. At least I think it was. My memory isn’t what it used to be.

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com [follow_me]